This is background information related to noise. View our latest analysis.

Noise can be defined as undesirable or unwanted sound and in many cases, is harmful to human wellbeing. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies environmental noise, originating from sources like road traffic, railways, aircraft, and industry, as one of the leading environmental risks to physical and mental health in the European region. It contributes to conditions such as cardiovascular disease, mental health issues, sleep disturbance, annoyance, and cognitive impairment.

Aircraft noise is mainly generated from two sources: the engine, and air moving over the airframe. This noise is exacerbated during critical phases of flight, such as take-off when greater thrust is required from the engines, or during landing when flaps and gear are extended resulting in increased air resistance. The UK has implemented internationally mandated and domestic environmental protection measures to manage the impact of civil aviation noise on local communities near airports.

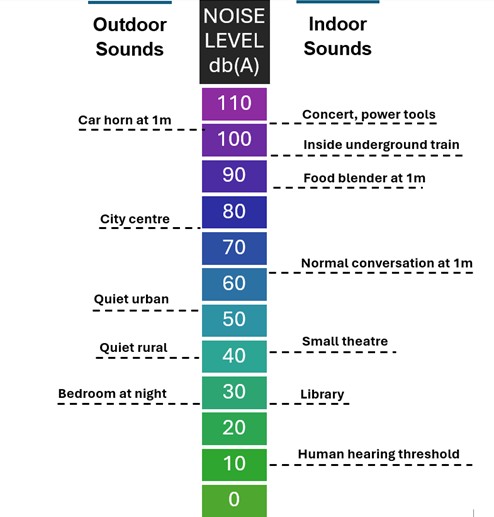

Unlike most other forms of pollution, noise pollution depends not just on the physical aspects of sound itself, but also on the human reaction to it. The level of sound is measured in decibels (dB). On the decibel scale:

- A doubling of noise energy results in an increase of 3 dB;

- A change of 3 dB is generally considered the minimum perceptible difference under normal listening conditions, although smaller changes may be noticeable in certain contexts; and

- A change of 10 dB represents a tenfold change in noise energy but is perceived by most people as a doubling or halving of loudness.

A-weighted decibels (dBA) are often used in measurements of aviation noise. This takes account of the frequencies that people are most sensitive to, as the human ear is less sensitive to sounds at low and high frequencies. Some examples of typical noise levels are outlined below.

Some noise impacts can be measured objectively (for example, sleep disturbance or hearing loss). Others, such as annoyance, are subjective and vary based on individual sensitivity, context, and perception. To assess these impacts, exposure-response studies are used to examine the relationship between a measurable level of noise exposure and the corresponding human response. These studies yield exposure-response relationships, which may be used to determine population impact levels and identify mitigation strategies. Consequently, various noise metrics are used to capture different dimensions of sound exposure and link them to specific health outcomes. More information on the noise metrics used to address aviation noise are described in the CAA’s Noise Metrics Guidance.